Sports

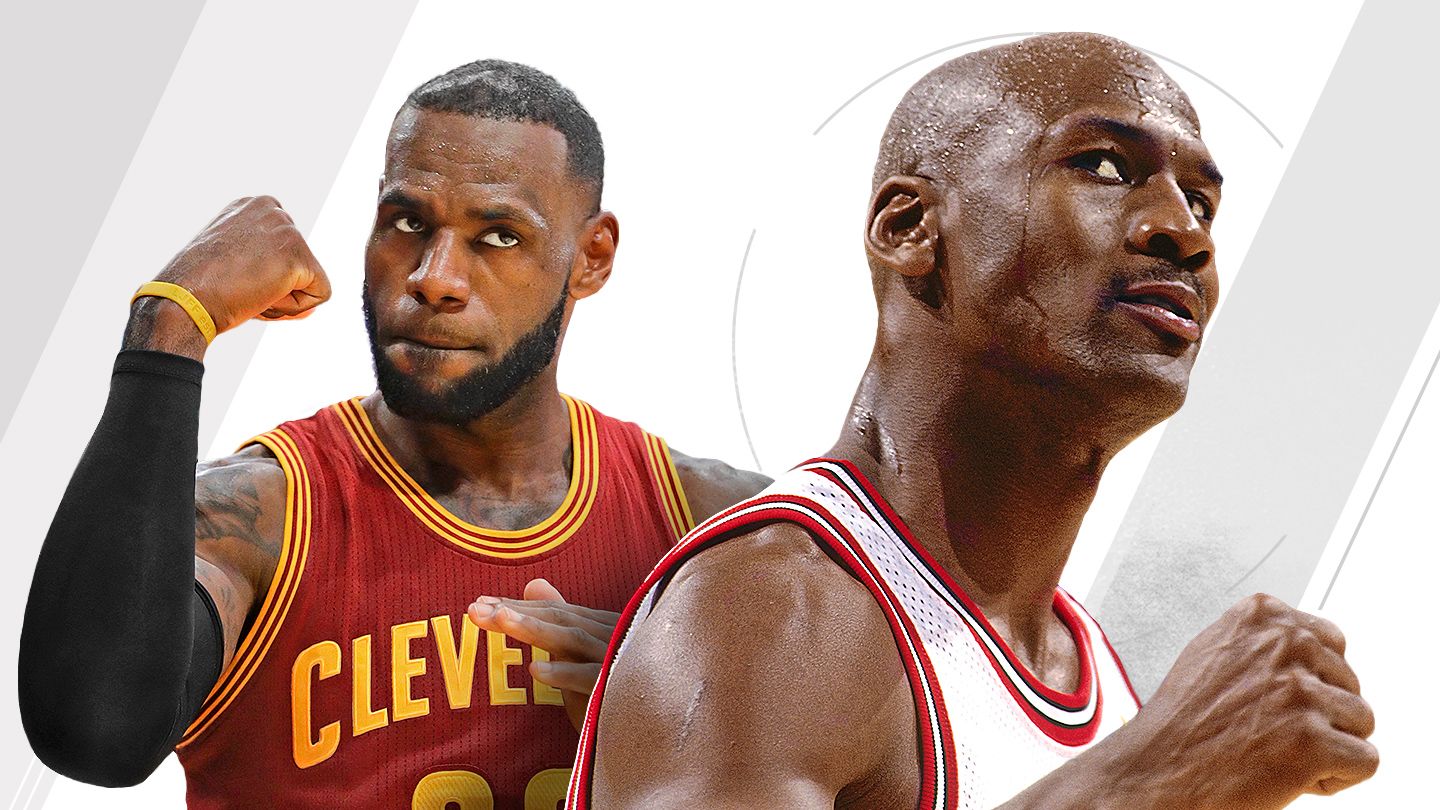

Is LeBron overtaking MJ as the greatest player of all time? – ESPN

Keith Olbermann weighs in on the most debated topic in sports: whether Michael Jordan or LeBron James is the greatest NBA player of all time. (3:58)

Who is the greatest NBA player of all time?

When Michael Jordan made his final shot for the Chicago Bulls 20 years ago next month, that question was easy to answer. While cases could be made for Bill Russell based on championship rings, Wilt Chamberlain on statistical dominance and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on longevity, the consensus was clear: Jordan was the greatest basketball player who had ever lived.

And then along came LeBron James, a challenger to the throne unlike any before him. The comparison between James and Jordan, once premature, is now fair to make. This is James’ 15th NBA season, matching Jordan’s total, and he has already played 71 more regular-season games and an incredible 49 more playoff games. With James still established as the league’s best player at age 33 and adding playoff game winners to his résumé seemingly by the week, the question is worth asking: Jordan or LeBron?

Two years ago, when ESPN was ranking the best players in NBA history (result: Jordan first, with James third behind Abdul-Jabbar), I developed a metric that could evaluate the league’s greatest stars throughout the decades on a level playing field. The result was championships added, which uses Basketball-Reference.com’s win shares to estimate how much a player added to his team’s chances of walking away with the title that season based on regular-season and playoff performance.

Back then, Jordan was first and James third by the numbers, too — although Chamberlain, not Abdul-Jabbar, occupied the spot between them. However, James has spent the subsequent two-plus years burnishing his legacy, most notably leading his Cleveland Cavaliers to the 2016 championship by upsetting Golden State in the NBA Finals after the Warriors surpassed Jordan’s 1995-96 Chicago Bulls for the best regular-season record ever. At the time, I noted James’ playoff run had pushed him past Chamberlain into second in all-time championships added.

Let’s take another look at James vs. Jordan by championships added (regular season and playoffs combined), going season by season.

Year by year, Jordan has had an edge over James throughout their respective careers. James narrowed the gap during their 10th seasons — that’s when Jordan returned for the final 17 games of 1994-95 after his first retirement — before Jordan pulled away during the Bulls’ second three-peat.

Because of the way championships added rewards only quality seasons, not mere accumulation of statistics, Jordan added almost nothing to his total by returning with the Washington Wizards at age 38. (His combined championships added in two seasons with the Wizards: .01.)

By continuing to play at near-peak levels so deep into his career, James has almost caught up. In terms of unadjusted regular-season and playoff championships added, the count through the end of the 2017-18 regular season was Jordan 4.74, James 4.48. If James can approximate last year’s playoff run (.35 championships added), he’ll pass Jordan in career championships added next month.

One takeaway from comparing Jordan and James by championships added is that Jordan’s current edge owes entirely to regular-season performance. Though James now has more career win shares than Jordan (he passed Jordan this season, moving into fourth all time behind Abdul-Jabbar, Chamberlain and Karl Malone), Jordan rates as adding more championships in the regular season because his value was more concentrated in his best seasons. That is to say, the contributions of MJ’s greatest regular seasons were more valuable, while LeBron has made up ground in cumulative value.

The two GOAT contenders are in a virtual deadlock in estimated championships added based on awards, the third component of the formula. Jordan (3.05) is ahead of James (3.01) due to his modest lead in career MVP shares. James will probably take the lead when this year’s MVP voting is factored into the equation.

That leaves playoff value as James’ strongest argument. His 2.24 championships added in the playoffs are more than those of Jordan (2.05) and everyone else in league history. That might be tough to square with Jordan’s six championships to James’ three, and James’ teams going 3-5 in the NBA Finals, but James comes out ahead for a couple of reasons.

First, James has simply amassed more opportunities in the playoffs by virtue of making deeper runs in seasons that ended short of a championship. While his advantage in games played owes slightly to the NBA expanding the first round of the postseason from best-of-five to best-of-seven after Jordan’s playoff career, James has already played in 43 playoff series to Jordan’s 37 — not including the upcoming Eastern Conference finals. And naturally James deserves the lion’s share of the credit for his teams winning enough to play in those additional series — and get more chances at the NBA title, including more Finals appearances than Jordan’s teams.

Second, for the most part, James’ teams losing on the biggest stage can’t be traced to his own performance. That tag was accurate in 2007, James’ first Finals appearance at age 22, and in 2011, when he struggled badly as the Miami Heat lost to the Dallas Mavericks. Since then, as measured by my wins above replacement player (WARP) metric, James’ performance in Finals his team lost (2014, 2015 and 2017) has compared favorably to Jordan’s performance in his team’s Finals wins — and even to James’ own during his three title seasons, when he’s won three Finals MVP trophies. That makes six Finals in which James’ performance has stacked up well with Jordan’s performance.

Though Jordan has a comfortable lead in Finals WARP per game played, James, by virtue of the two extra appearances, has accumulated more WARP in the Finals (10.9) than Jordan (10.1) or anyone else since the ABA-NBA merger.

The respective camps in the Jordan-LeBron debate reach their most frenzied pitch when they discuss which player had a harder time dominating in his era. To hear Jordan’s supporters tell it, defenders were allowed open fisticuffs to prevent him from getting to the basket. Meanwhile, James’ defenders would have you believe that Jordan was beating five guys from the Y to win his championships.

There’s a kernel of truth in both arguments. Physical defense was more commonplace in Jordan’s heyday, when handchecking was tacitly permitted despite being officially banned. At the same time, the sophistication of NBA defenses has increased dramatically since the illegal-defense rule was eliminated in 2001. It’s impossible to say exactly how James might have reacted in an era with less floor spacing and more physical play, or whether a modern Jordan might have relied more on a 3-point shot than getting to the basket.

That said, accounting for quality of play is an important factor in the GOAT discussion. For instance, without any timeline adjustment for championships added in the playoffs, Jordan would fall behind George Mikan, who dominated a growing NBA still in the process of integrating racially.

So I adjust for league quality based on whether returning players play more or fewer minutes per game. When the league improves, minutes per game go down for returnees. When it declines, as with expansion, they tend to play more minutes per game.

Because Jordan and James weren’t separated by much time, the difference isn’t as dramatic as with Mikan. Yet James’ leagues still rate on average as 12 percent better than Jordan’s, which makes sense given the influx of international talent in that span. I estimate the pool of talent from which the NBA draws players has grown by 28 percent since 2003, while the league has added just one team.

When I adjust for league quality, James is no longer merely on the verge of catching Jordan as the greatest player in cumulative value. He already has Jordan in his rearview mirror, with 4.66 total championships added to Jordan’s 4.28.

Part of the challenge of the GOAT debate is definitional: Does it refer to the player who reached the greatest heights, or the one who had the best career?

In the hypothetical where we’re choosing sides to win a single game or series, like “the Martian premise” Bill Simmons employs in “The Book of Basketball” pitting the best possible team of NBA players against aliens, Jordan remains the pick. His 1990-91 season was the best we’ve ever seen — a superstar combining sheer individual greatness with the ability to (begrudgingly, perhaps) fit into the team concept of Phil Jackson’s triangle offense.

The alternative hypothetical is this: Imagine a draft where we’re picking every single NBA player at the start of his career. The team gets the player’s career exactly as it played out, with no chance of anyone taking his talents to South Beach. This is exactly the question championships added is trying to answer, and to the extent it’s close now, James’ eventual superiority is all but inevitable. After all, look at what happens when we graph championships added by age instead of experience.

Now, James comes out ahead at every age, thanks in part to starting younger but also because he reached peak performance sooner. Before adding in this season’s playoffs, and without the adjustment for league quality, James already has more championships added through his age-33 season than Jordan did at 34. Barring injury or an improbable decision to walk away from the game as MJ did, James will soon pass Jordan in career points. He’s already ahead by a wide margin in career rebounds and assists.

A team drafting James’ entire career would assure itself championship contention for more than a decade given his metronomic consistency and ability to avoid injury. Jordan might have been better at his best, but James has already put together the best NBA career we’ve ever seen.